CAVE

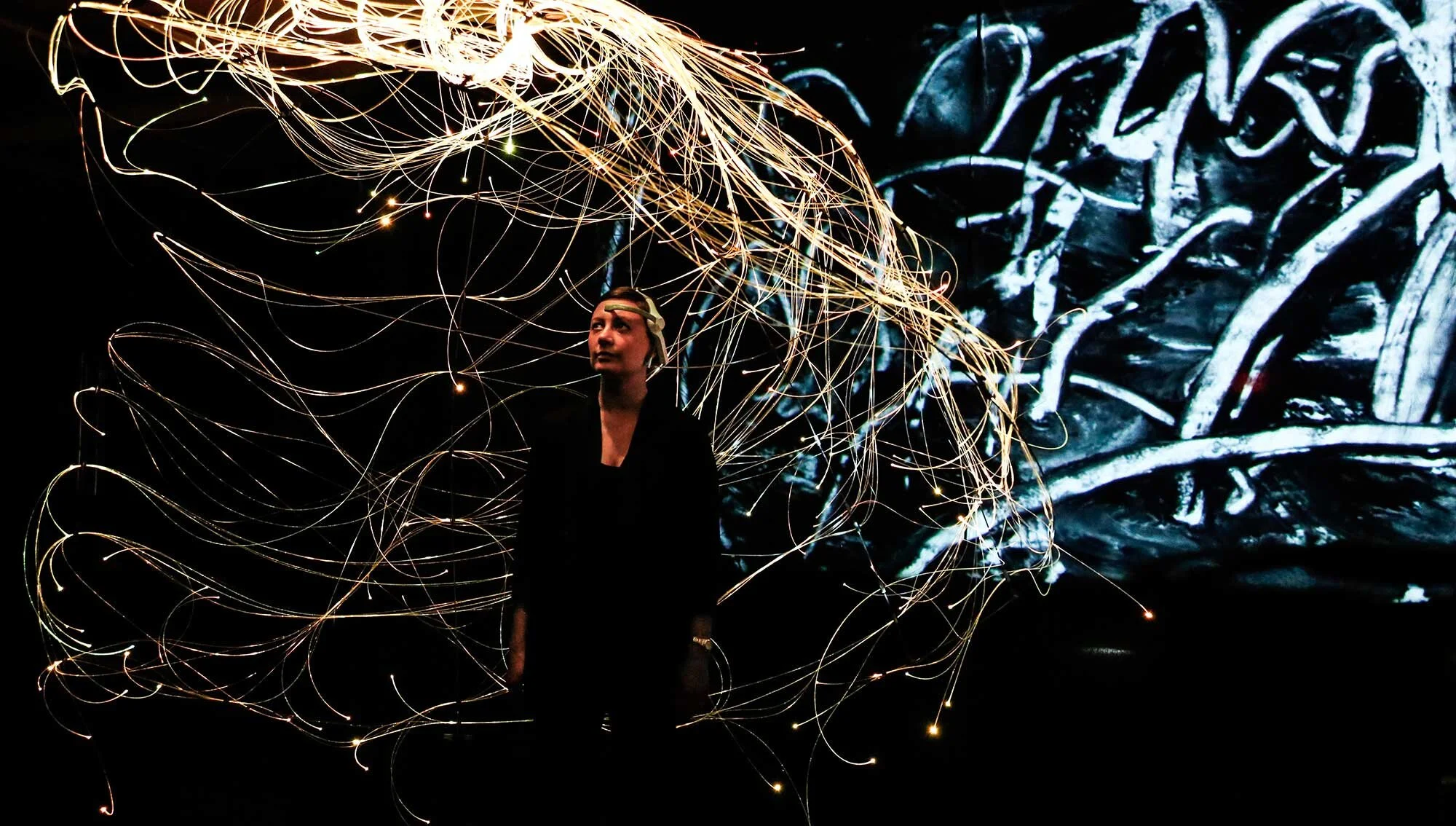

Installation shot of Jessica standing in a neuro-cave with the CAVE video in the background

The NeuroCave Collaborative

www.montana.edu/cave

Sara Mast (visual artist)

Jessica Jellison (architect)

Bill Clinton (fabricator)

Jason Bolte (composer)

Linda Antas (composer)

Zach Hoffman (photographer & video editor)

John Miller (neuroscientist)

Brittany Fasy (computer scientist)

David Millman (computer scientist & engineer)

Chris Huvaere (computer programmer)

Barry Anderson (video artist)

Chris Comer (neuroscientist & science advisor)

In Fall, 2015, I initiated CAVE, a collaborative, interdisciplinary artscience project that engaged several of my colleagues both at MSU and beyond. As the lead visual artist for this project, I wanted to merge the ‘mind’ of 35,000 year old cave art with current brain research. The Neuro-Cave Collaborative developed an interactive, multisensory work in which the viewers’ brainwaves (through the use of neurofeedback headsets) generate light and sound in an immersive environment that spans cultural memory from humanity’s earliest creations in the cave to today’s most technological creativity. This collective experience in which the viewer contributes to the work blurs the boundaries between art and artist. CAVE unifies the viewer’s neurological processes in real time within a shared environment of five neuro-caves. When brain coherence is reached between the viewers in the space, a resonant tone is activated. CAVE reflects upon the communal nature of human creativity, from the earliest tools and materials to those of today--from spit, hand, charcoal and pigment to fiber-optic cable, video and electronic sound. Though much has changed, the creative impulse lies at the root of both.

Abstract

CAVE is a collaborative, interdisciplinary artscience installation that merges the ‘mind’ of 35,000 year old cave art with current brain research. The Neuro-Cave Collaborative (2017) developed an interactive, multisensory work in which the viewers’ brainwaves (through the use of neurofeedback headsets) generate light and sound in an immersive experience that spans cultural memory from humanity’s earliest creations in the cave to today’s most technological creative expression. This communal experience in which the viewer contributes to the work blurs the boundaries between art and artist. CAVE unifies the viewer’s neurological processes in real time within a collective environment of five neuro-caves. When brain coherence is reached between the viewers in the space, a resonant tone is activated. CAVE reflects upon the collective, ongoing nature of human creativity, from cave paintings composed with humanity’s earliest tools of charcoal, pigment and drums to today’s highly technological creations of fiber-optic cable, video and electronic sound. Though our tools have changed dramatically, the creative impulse endures.

Detailed Description

Within a darkened gallery space, the viewer enters human-scaled sculptural forms (neuro-caves) created from light-emitting fiber optic cables & Emotiv brainwave readers, color coded to track brainwave activity (data visualization) and generate a tone (data sonification). Simultaneously, the viewer sees and hears the neurofeedback of others in the space reflecting the group’s brainwave activity. This group measurement reflects co-variance, a trending area of interest in neuroscience. An immersive, ‘moving painting’ that echoes the cultural memory of humanity’s earliest art in the cave morphs cyclically around the room, creating a haptic sense of time’s passage. This multisensory experience of mutually-generated (viewers and makers) sound and image interactions elicits viewer discovery, creativity and communal experience. The gallery is redefined as a creative artscience lab and acts as a scientific instrument as well as engaging the viewer in time and memory. The viewers, both individually and collectively, may track and alter their own visual and experiential reality based on the neurofeedback. When co-variance is reached, a resonant chord is formed by the individual neuro-caves, and the combined tones and colors reflect the level of co-variance between the individuals within the whole space.

Project Inspiration

In October, 2013, National Geographic published an article entitled Were the First Artists Mostly Women?

https://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2013/10/131008-women-handprints-oldest-neolithic-cave-art/

Handprints in eight cave sites in France and Spain were analyzed by Dean Snow of Penn State University, and three quarters of those handprints were left by women. This represents a new genesis of art history and women’s contribution to it. “People have made a lot of unwarranted assumptions about who made these things, and why”, stated Dean Snow. As a woman painter, this revision of the origin of art in the cave struck a chord. Though they may never be answered, it raised questions for me that CAVE asks the viewer: If not a male shamanistic ritual for the hunt (as has long been assumed), what was the purpose of these works? How do these elegant drawings and signs challenge the notion of primitive, uncivilized artists? How does the context of the cave situate the meaning of this work? Why the darkest, deepest caverns and not the walls outside? Did sensory deprivation and/or altered states of being play a role in the process? Why the indecipherability of particular forms in a static sense, and instead shape shifting, parallel lines with multiple overlapping depictions that imply movement? Why is the highest production of these paintings in the most acoustically resonant parts of the cave? Were the echoes in caves a mystery to which the groups responded with sounds of their own?

Reproductions of cave paintings we see are often misleading–the cave walls were not neutral supports for imagery, but instead provided natural folds as animal outlines to which a few strokes were added to supply the missing parts. The interaction between the actual cave spaces and the artists was profound–the forms of the cave architecture itself were engaged as “living membranes between the realms” (David Lewis-Williams, The Mind in the Cave). Marc Azema, archaeologist at University of Toulouse Le-Mirail, France, has studied the sequential nature of the cave drawings and concludes in his book La Prehistoire du Cinema that cave paintings are our first animations. Could the first artists, likely women, have been bringing the animal forms to life in the first animations, using through the animating flicker of torch light? Rather than a means to gain ‘power over’ their fellow creatures, are these paintings feminine expressions of empathy, reciprocity and a deep recognition of interdependence with the ‘more-than-human’ world?

The predominance of animal images in cave art demonstrates the significance of that primary relationship that both sustained and preyed upon early humanity. Now, facing the sixth extinction, modern life has exchanged that mutuality with other living creatures for a relationship to our own technologies. As Kevin Kelly states in What Technology Wants, technology is “…a vital spirit that throws us forward or pushes against us. Not a thing, but a verb”. A new shape shifting is underway. The cave artists remind us to both honor and remain humble before that which both sustains and preys upon us.

Perhaps the cave paintings are humanity’s earliest expressions of empathy, mutuality and deep interdependence with the non-human world. Could the first artists, likely women, have been bringing these forms to life in the first animations, using the flickering torch light within the cave to mimic their movement? These paintings were not only humanity’s first images, they were our first art installations, our first films and our first architectural spaces.

CAVE ponders the collective nature of human creativity from the first artists in the cave to today’s contemporary, interactive expression possible only through technological means. Time and space continue to unfold new tools and intentions, yet what remains fundamentally human is the creative impulse and the desire to make one’s mark.